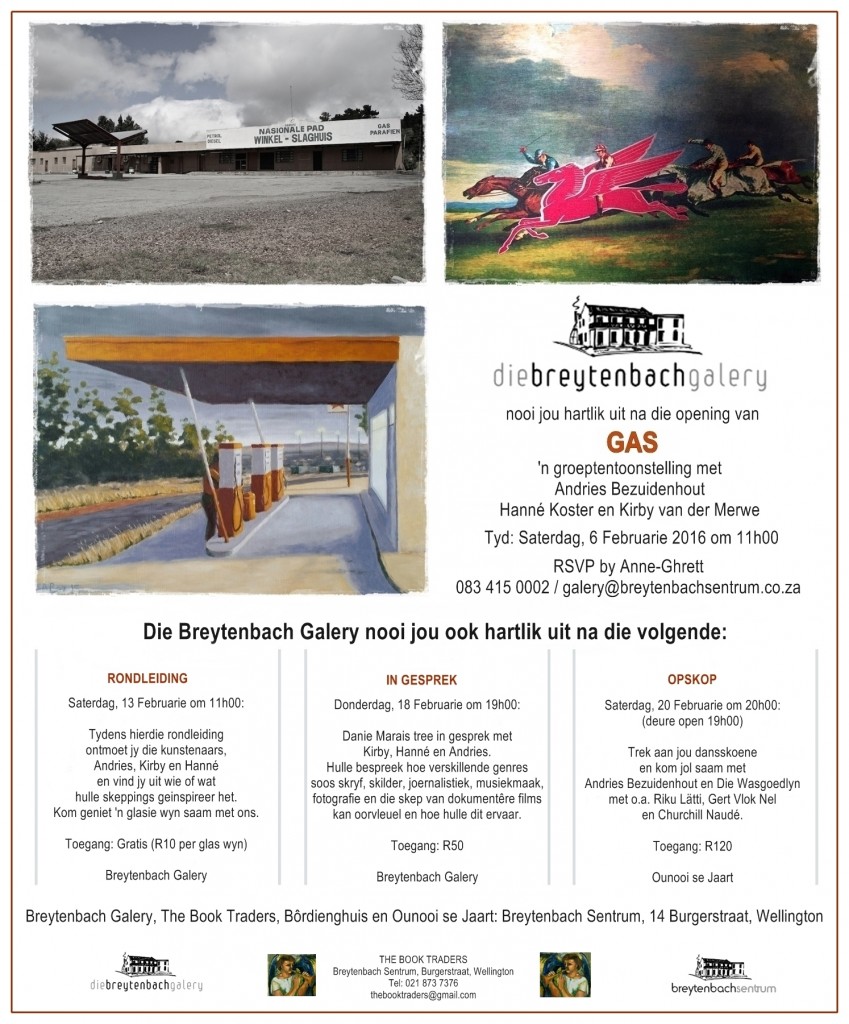

!["Brandstof" [Fuel], oil on canvas, 30x40cm](https://andriesbezuidenhout.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/rBrandstof-1024x766.jpg)

Andries Bezuidenhout on his contribution to the exhibition:

gas gases, n. gas; (Am.) brandstof, petrol

gas gaste, n. guest, visitor

gas gasse, n. gas

JM Coetzee writes in his novel Elizabeth Costello: “Realism has never been comfortable with ideas. It could not be otherwise: realism is premised on the idea that ideas have no autonomous existence, can exist only in things. So when it needs to debate ideas, as here, realism is driven to invent situations – walks in the countryside, conversations – in which characters give voice to contending ideas and thereby in a certain sense embody them” (p. 9). Or paintings. The title “Gas” draws on Edward Hopper’s painting with the same title, a work characteristic of the American painter’s realist approach to depicting landscapes. Hopper completed this painting of a rural filling station in 1940. A lonely figure guards three fuel pumps at sunset. Electric light from the filling station contrasts with natural light at dusk. A dense forest blocks the horizon.

When we look at Hopper’s painting today it most probably calls up different connotations to those of a typical art enthusiast of the 1940s. Environmental concerns and the ecological impacts of fossil fuels are at the forefront of present day collective consciousness. Fuel stations have already changed in form and design. In the near future filling stations will, in all probability, no longer be places where we are required to interrupt our journeys. This may be a cause for feelings of nostalgia, but their ruins will also remind us of why we use the word anthropocene to name the current era.

The South African context also calls up pertinent issues around the use of non-renewable sources of energy: coal, oil, the impact of fracking on water sources, etc. I’ve been working on landscape paintings that explore how that which we observe on the earth’s surface is related to that which we pump and dig from below the surface in order to move “forward” – to progress, or to regress? I have also been exploring these issues in my poetry and music.

“Gas”, when spoken in Afrikaans, may also mean “guest” or “visitor”. The landscape painter is a visitor, at times a guest, an outsider’s eye that travels with a vehicle propelled across the landscape by a diesel engine in order to stare, to photograph, to paint. The anthropocene era forces us to be more aware of the tension between our status as guests or proprietors of the planet we inhabit. The human being as colonial animal, invader species, parasite. It’s about land, landscapes and possession. Who decides what happens to mineral and water resources? Terms such as “water rights”, “mineral rights” and instruments such as cadastres codify and control nature and other people in a symbolic and violent order. On the landscape itself fences, walls and warning signs are erected as instruments of control. Locating Hopper’s “Gas” in contemporary South Africa would imply eucalyptus trees and Apollo lights over an informal settlement on the horizon.

Landscape painting is typically seen as a conservative and nostalgic artistic genre. Maybe a different way of viewing landscapes (Hopper’s landscapes, but also contemporary realist landscape painting) presents different possibilities. Then again, realism can only deal with the concrete, the landscape, the conversation.

Opening: Saturday 6 February 2016, 11:00

Where? Breytenbach Sentrum, 14 Burger Street, Wellington, South Africa

RSVP: Anne-Ghrett 083 415 0002 / galery@breytenbachsentrum.co.za